|

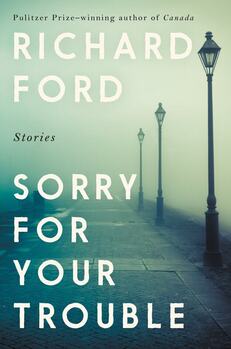

In this just-released collection of short and long stories, Richard Ford returns to a form he explored more often early in his career, before the Frank Bascombe novels that brought him the Pulitzer Prize for Independence Day, and the wonderful subsequent novel Canada, which may be his best work if The Sportswriter isn’t.

The opening story here, “Nothing to Declare”, tells the tale of a chance encounter with an old flame, and the afternoon walk they share through the French Quarter and along the Mississippi. Sandy McGuinness spots a woman he hasn’t seen since a school-break trip to Iceland that ended their relationship. They meet by chance decades later in a noisy bar where Sandy and some law firm colleagues are drinking. She’s drunk enough, and he’s open enough, for this to turn into most anything. And what it turns into is an account of their respective ambivalences, not-quite-regrets and wondering-what-ifs, all told in snippets of laden and open-ended dialogue, narrated in language that pulls us into the heads and hearts of each of them, in what writers call a “free indirect style” that colors in around the edges. Each takes the measure of the months they had and the decades they missed. “Happy” is named after a dour and too-often-unpleasant woman, Bobbi Kamper, who for many years has peopled the periphery of a group of now-aging artists and writers and the like. Her husband Mick, with whom she’s not lived for some time, gave her the nickname in irony, a commodity he traded in while editing for a significant publishing house after his own novel did okay many years ago, but he couldn’t come up with another. Over the course of a last night in Maine before heading back to their lives in New York and beyond, they all look back not very wistfully, and forward uncertainly, after a tepid toast to Mick’s recent passing. In the first of two long stories, “The Run of Yourself” explores life after losing one’s wife of many years, with so many more to go. Peter Boyce takes a summer rental on Cape Cod, near the one they had rented for years and Mae died in two years back. He recounts her battled with breast cancer, her courage near the end, and the way she chose to go. He decides to leave early, drive straight through to their home in New Orleans, then stays. “Small, graduated adjustments were all he needed” to go on. “Not that Mae, here or gone, was a small matter. She was now his great subject. But why she’d done what she awfully did was, at this day’s end, not business she’d wanted to share. And not business he could do anything about. There was nothing further to learn or imagine or re-invent around here. Love now meant only to take in and agree.” In something of a return to the territory of Ford’s first collection of stories, Rock Springs, “Displaced” is the tale of a sixteen-year-old boy, who tells us about life after losing his father. The story itself is activated by the presence of a not-much-older Irish immigrant hooligan, Niall, who lives for a time in a rooming house across the street in Jackson, Mississippi. It begins: “When your father dies and you are only sixteen, many things change. School life changes. You are now the boy whose father is missing. People feel sorry for you, but they also devalue you, even resent you—for what, you’re not sure. The air around you is different. Once, that air contained you fully. But now an opening’s cut, which feels frightening, yet not so frightening. “And there is your mother and her loss to fill . . .” Niall dubs our protagonist “ole Harry” and takes him under his wing at the widow’s urging. They take the taxicab Niall drives for a living (because his own father is a drunk) to a drive-in movie night, where “Harry” is taken with Niall’s cool and cocky demeanor. “He had a natural understanding of whatever stood in front of him.” But Niall has secrets of his own, and after a scrape with the law and a short stint in the military at the suggestion of a judge, he’s written that he’s gone to New York to catch a freighter back to Ireland. “When I read the letter, I wondered what kind of boy would I say Niall MacDermott was. We go through life with notions that we know what a person is all about. He’s this way—or at least he’s more this way than that. Or, he’s some other way, and we know how to treat him and to what ends he’ll go. With Niall you couldn’t completely know what kind of boy he was. He was good, I believed, at heart. Or mainly. He was kind, or could be kind. He knew things. But I was certain I knew things he didn’t and could see how he could be led wrong and be wrong that way all his life. ‘Niall will come to no good end,’ my mother said a day after his letter came. Something had disappointed her. Something transient or displaced in Niall. Something had been attractive to her about him in her fragile state, and been attractive to me, in my own fragile state. But you just wouldn’t bank on what Niall was, which was the word my poor father used. That was what you looked for, he thought, in people you wanted closest to you. People you can bank on. It sounds easy enough. But if only—and I have thought it a thousand times since those days, when my mother and I were alone together—if only life would turn out to be that simple.” This is Richard Ford, still doing it—and teaching it to some fortunate ones indeed at Columbia—after all these years.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Matthew GeyerMatthew Geyer is the author of two novels, Strays (2008) and Atlantic View (2020). . Archives

April 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed